Why Every Prophet was Insulted

- Hamze Kassem

- May 4, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 22, 2025

He does not come with an army. He comes with a voice. With words that cut like knives because they strike a wound everyone knows—but no one wants to see. The man of God. He speaks for God—against the world. And the world responds: with mockery, with contempt, with destruction.

A wave of videos and commentary has flooded the internet since Abdullah Hashem Aba Al-Sadiq delivered his speech—a day after the Pope's death—in which he declared himself the true Pope. That no one but the man chosen by God has the right to rule: spiritually and politically. A day after believers in the Ahmadi Religion of Peace and Light raised the Black Banners—foretold by the Ahlul-Bayt —in St. Peter’s Square, inscribed with the words: “Loyalty belongs to God alone.”

Since the dawn of history, societies have met prophetic figures with the same reflex: rejection. Not out of intellectual doubt, but from instinctive defense. For the man of God does not merely ask questions—he questions everything. Morality. Power. History. Identity. And that makes him a target. Then and now.

The Bible, the Qur'an, the Torah, and the Bhagavad Gita do not merely recount the stories of great spiritual figures. They document their societal downfall. A destruction that may not begin with physical violence—but always begins with media, words, social exclusion, and moral attack. Prophetic voices were mocked, slandered, criminalized. They became mirrors for fear, hatred, envy—and society’s deep inability to face itself. What we see in today's media landscape echoes the ancient patterns surrounding the men of God.

Many Revelations, One Pattern

In the Torah, Moses is doubted by his own people. “Who made you ruler and judge over us?” (Exodus 2:14) they ask, when he tries to mediate between two Hebrews. This question—brimming with distrust and defiance—follows his entire mission. Moses, who speaks with God, remains a suspect in the eyes of his people. Later, he watches them build a golden calf at the very moment he is receiving God’s law on Mount Sinai. This is the tragedy of the prophetic experience: while the prophet wrestles with God, the people replace God with an idol. Today, there may be no golden calf—but the pattern remains. Man-made systems dominate every domain.

In the New Testament, Jesus is accused of being a liar and a blasphemer. “We have a law, and by that law he must die, because he claimed to be the Son of God.” (John 19:7) But it did not end there. He was called “a glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and sinners” (Matthew 11:19), and his powers were demonized: “It is only by Beelzebul, the prince of demons, that this man drives out demons.” (Matthew 12:24). The public discourse surrounding Jesus was saturated with disinformation and moral delegitimization—a phenomenon we would today call character assassination. And just as Jesus was seen as Beelzebul, is the man of God today labeled the Antichrist?

The Prophet Muhammad faced relentless opposition in his time. The Quraysh called him a liar (Qur'an 6:25), a sorcerer (74:24), a madman (68:2), a storyteller (83:13), a misguided man (34:8), even merely a poet (37:36). In Surah 52:29 we read: “Or do they say: ‘He is a poet! So let us wait for the misfortune of time to befall him.’” These labels had one purpose: torender his message irrational, illegitimate, and dangerous. Are these not the same traits peoplenow attribute to the Dajjal?

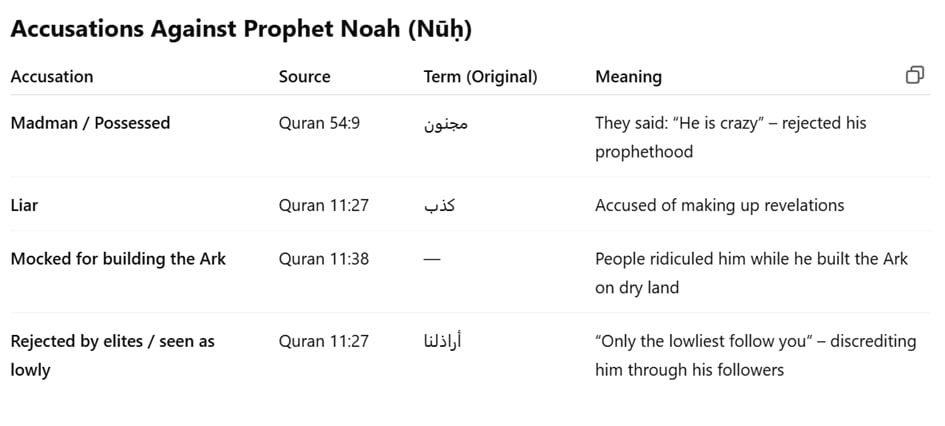

Noah, too, was mocked when he began to build the ark (Genesis 6–9). In the Qur'an: “And every time a group of his people passed by him, they ridiculed him.” (Qur'an 11:38).

Abraham was persecuted as a destroyer of idols (Qur'an 21:57–68), as a rebel against ancestral tradition (Genesis 12). His own father cast him out. He was thrown into the fire. The prophet as a family wrecker—a label still used in modern debates about religious movements.

Why Most People Hate the Men of God

The "shadow" in psychology is the unconscious part of ourselves that holds everything we reject. The man of God, then, becomes the collective shadow-bearer. He reminds us of what we do not wish to be: uncomfortable, truthful, vulnerable. And this is where the violence against him is born.

The psychological reaction to the man of God is ancient: denial, mockery, projection, elimination. The men of God challenge us to face guilt, repentance, fear, and responsibility. But the ego, self-sufficient and proud, cannot bear this. So it discredits the source of the discomfort.

A man of God who preaches unity is today called the Antichrist. Yet perhaps it is our extreme individualism that is the true Antichrist. One who calls for material renunciation is deemed unrealistic. The ego resists. Muhammad was criticized in the Qur'an (38:7) as a bringer of innovation: “We never heard of this in the last religion. This is nothing but an invention.” A classic projection: the man of God does not destroy order—he reveals that none truly exists. Except one: God is One, and He alone appoints His representative on earth.

The man of God is always a revolutionary—not in the sense of violence, but in radical critique. His message is rarely system-compatible. He does not preach improvement—he calls for repentance. Not a better system, but a new heart.

Today, the man of God is still persecuted—now in digital spaces. The result is the same: exclusion. Those who speak against the mainstream are often “cancelled.” The digital inquisition is faster, broader, and more anonymous—but its principle remains unchanged: it judges before it understands.

Muhammad was seen as a political agitator who “divides communities” (Qur'an 38:4), who spread “tales of the ancients” (6:25), and who only sought power. Jesus was accused of inciting rebellion (Luke 23:2). Moses threatened the Pharaonic order (Exodus 5:1–9). Prophecy and state have always clashed.

“What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.” (Bible, Book of Ecclesiastes, Chapter 1, Verses 9–10)

The pattern persists: whoever speaks an uncomfortable truth becomes a target.

Consider Julian Assange. He revealed what was never meant to be revealed. The response: isolation, defamation, imprisonment. Or Greta Thunberg—a child who became a moral authority, only to be met with mockery, hate, and threats. Whether or not one agrees with their message, the mechanisms of rejection are the same.

The man of God no longer walks through the desert. A tweet, a video, a manifesto is enough. Yet the journey remains unchanged: from voice to solitude. From protest to exile. From word to cross? As in all ages, there are at first only a few believers who stand firm. So it was with Jesus and Muhammad.

What is the solution? To listen. To understand. To discern. Every voice deserves to be heard before being judged. Let the strongest argument prevail. We must relearn how to distinguish truth from madness. Fanaticism from depth. Manipulation from revelation. This requires education. Mental training. Spiritual maturity. And the courage to correct errors rather than defend them. The man of God is often alone. But his voice is essential. For God is still speaking. But we have become too loud to hear Him.

It remains the task of a spiritually awake, intellectually mature society to resist dismissing prophetic voices too quickly. For the man of God does not speak against us—but for us. Against what we have become, so we may become what we are meant to be.

Until then, the words of Jesus remain true:

“A prophet is not without honor except in his own town, among his relatives and in his own home.” Bible, Book of Mark, Chapter 6, Verse 4)

And the Qur'an confirms:

“Those before them said the same: ‘He is but a man like yourselves.’ But they mocked him.” (Quran, Chapter 23 (Al-Mu'minun), Verse 24)

It is time to break the cycle of rejection—not by calling every voice divine, but by relearning how to listen before we condemn.

For God has never stopped speaking. We have simply forgotten how to be still.

This was an excellent article...history often repeats itself. I pray that this time the people would learn from the past and bring about a better future. Thank you for this article. God bless you ♥️ 🙏🏼